Article by PHSNE Board Secretary Larry Woods

The Polaroid Big Shot is a single-purpose camera designed to take only one type of picture—a head and shoulder portrait of a person. Neither the film nor flashbulb it uses is still manufactured. However, it was famously used by Andy Warhol, and because of that, the Big Shot is still well known, and used cameras sell on eBay for five or ten times its original price. It can use only one type of film—Type 108 (and 669) Polaroid Color ISO 75 peel-apart film or the Fuji FP-100C equivalent. It also uses a Magic Cube flash and, in fact, needs to use a flash for each picture.

The camera has a rigid plastic body 10-1/4 inches long with a 220mm f/29 single-element plastic lens permanently set to focus at 38 inches. F/29 is not a typo and explains why you need a flash for each shot. There is no exposure adjustment except for the standard Polaroid “lighten-darken” control that allows you to vary the exposure up or down by two stops. The shutter has only one speed.

There is also a split-image rangefinder set to 38 inches with no moving parts. To focus the camera, you look through the viewfinder and then do what is called the “Big Shot Shuffle”—you walk backward and forward until you see a single image in the rangefinder, then shoot.

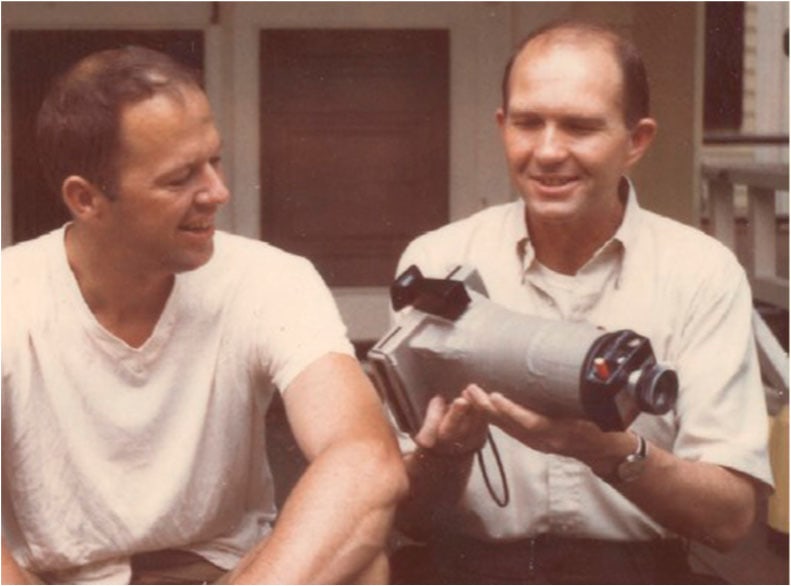

camera put together in Abele’s basement

In his 12-page article in the 2016 PHSNE Journal (#174), Dave DeJean noted that “mad genius” Bill Shelton, with help from fellow Data Processing colleague Bruce Abele, took the concept to prototype state. Bruce Johnson from Design and Manufacturing helped turn the “duct tape” photo into the Big Shot. Professional designers worked on the project for two years, keeping the 220mm lens at the original designer’s insistence, until the Big Shot was released in 1971. It stayed on the market for only two years, though because of Andy Warhol’s involvement, Polaroid apparently arranged to supply or repair cameras for him for several years beyond that.

This was a low-cost camera that came out toward the end of the peel-apart pack-film camera era. (The SX-70 came out in 1972.) Besides the single-element lens, it has a single-speed shutter and cheap spreader bars—the parts that squeeze the chemical pods and spread the chemicals on the film. Pulling the film out of the camera straight, allowing the chemicals to spread evenly, is evidently difficult. To aid in pulling the film out, there is a “whale tail” T-handle attached to the back of the camera. You hold the handle instead of the camera when pulling the film out. Unfortunately, on many cameras today the T-handle has broken off. It turns out that the spreader bars can easily be replaced with spreader rollers from a more expensive pack-film camera. This will help the chemicals spread more evenly.

The camera has one other feature: there is a 60-second timer on the back of the camera. After you pull the film out of the camera, you set the timer, wait for it to go off, and then peel the picture from the negative.

The camera is still usable today. The film (Polaroid 108, Polaroid 669, or Fuji FP-100C), decades past its expiration date, and Magic Cubes (not “Flash Cubes,” which require a battery in the camera) can be found on eBay, though at high prices. Check that the spreader bars or rollers are clean, load the film, install a Magic Cube, do the Big Shot Shuffle to focus, and press the shutter. Pull a film tab, then pull the film itself out of the camera, set the timer, and when the timer goes off, peel the film apart. It’s easier than it sounds.

Andy Warhol would do this up to hundreds of times with someone who commissioned him to do a silk screen portrait. He would then pick out one print, send it to a silk screen printer to create the enlarged portrait, which he would then add paint to.

What the heck…

Are Those Even Cameras?!

Join the PHSNE Newsletter and learn more about photographic history and preservation. Already an expert? Come and share your collections and knowledge as we celebrate the history and advancement of photography.